A Pilgrimage to Death Row Inside and Outside

|

|

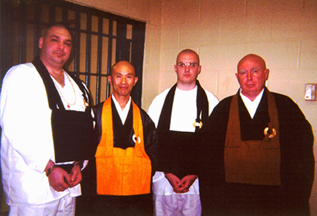

| Dainin Jack Jones, Ven. Shodo Harada Roshi, Koson Damien Echols and Ven. Kobutsu Malone Zenji Death Row, Tucker-Max prison, Tucker Arkansas. |

| Photo By: Rev. Daichi Storandt - September 19th 2000 |

by Kobutsu Malone, in collaboration with Dakota Rowland. |

|

The death house of the Arkansas Department of Corrections is an odd place to begin a Dharma legacy, but in America, Buddha Dharma moves in remarkable and unique channels. This story begins, in a way, with the execution of Jusan Frankie Parker - It actually begins long before he was executed - in his intense practice for over eight years on death row. Many of the currents in this channel of Dharmic flow extend from this remarkable human being, himself a killer, who by his own efforts transcended his karma and internalized oppression through the practice of zazen while on “the row” awaiting the executioner's needle. |

|

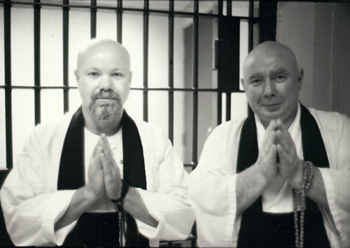

| Ven. Jusan Parker Zenji and Ven. Kobutsu Malone Zenji Death Row, Tucker-Max Prison, July 1996. |

| Photo By: Tom McKitterick |

Jusan affected many lives from his cell, both in and out of prison. Our present story involves two condemned prisoners who were inspired by Jusan, and the abbot of a three-hundred-year old Japanese Rinzai Zen Monastery, all of whom have been profoundly affected by Jusan’s Bodhisattva spirit. Shortly after witnessing Jusan’s execution on the night of August 8, 1996, I wrote several stories about my experiences with him and the experience of witnessing his murder in the Arkansas “death chamber.” I also spoke to many people about the events, including my close friend Rev. Kyogen Carlson, the Abbot of The Dharma Rain Zen Center in Portland, Oregon. After talking with Kyogen and sending him copies of what I had written about Jusan and the execution, Kyogen happened to serve as the host for Venerable Shodo Harada Roshi, the Abbot of Sogen-Ji Monastery, in Okayama, Japan. Evidently, Kyogen told Jusan’s story to Harada Roshi on a trip from the airport in Portland during Roshi’s visit to the Dharma Rain Zen Center. It seems that Harada Roshi was deeply moved by Jusan’s story, and used it many times afterwards in lectures and formal Teishos. It was through this series of events that Venerable Harada Roshi contacted me and laid the foundation for a “Dharma relationship,” which has deepened and ripened in the intervening time. In 1999, I received an invitation from Harada Roshi to travel to Sogen-Ji to teach there and offer, for the Japanese people some lectures on the death penalty. In return for this profound honor, I offered an invitation to Harada Roshi to come and visit the Arkansas death row to serve as the preceptor for a Jukai ceremony for two of my students confined there awaiting execution. These men, Jack Jones and Damien Echols, both initially became practitioners through their interaction with Jusan. I had been in correspondence with them through The Engaged Zen Foundation and had visited with them both several times as I was able during some marathon drives to various prisons when finances and the generosity of supporters enabled me to make such trips. For almost six months this past year, I had been in correspondence with Harada Roshi and his translator Rev. Daichi Priscilla Storandt "Chisan" concerning setting up a visit, a “pilgrimage” as he refers to it - to the Arkansas death row. Arrangements with prison authorities and a myriad of details had to be worked out to make this pilgrimage possible. There were countless difficulties encountered on this path, but we were able to transcend them all and Harada Roshi was able to visit the Arkansas death row with unprecedented access to its high security environment on September 19, 2000.

The story of Harada Roshi’s pilgrimage:Dakota Rowland and I, compadres, prison abolitionists, and social activists, traveled to Memphis a day before Harada Roshi’s arrival in order to secure rooms and to be well rested to greet him and Chisan the next morning. I had booked rooms in the Comfort Inn Airport/Graceland. It was only after arriving the afternoon of the 18th that we realized that we had checked into a motel bracketed by two rather large strip clubs, one of which advertising “Gentlemen: show your hotel key and get free admission.” Dakota remarked, [“It’s like it’s a done deal.”] We went for a long evening walk, with the intention of finding a bus that would take us into downtown Memphis but wound up walking up “Elvis Presley Boulevard.” The “Boulevard” is a seedy, tacky affair, comprised of a seven-lane highway lined with auto dealerships, cheap eating joints and strip-malls. I chuckled as we passed the Elvis Presley self storage business. Would the “King” ever use such an establishment? Graceland, the home of the “King,” was an amazingly grotesque affair. Directly across the street from it are parked two airplanes that Elvis had used that now are open for tourists. At the south west corner of the Graceland estate was a podiatry clinic that had obviously been converted from a Dairy Queen, the distinctive barn-like DQ architecture still evident. We walked for several miles, looked at various places to eat and settled on a small family-owned pizza place offering “The best pizza in Memphis.” We ordered our dinner of pizza and salad under the watchful eye of an armed security guard, whose presence was intimidating and spoke of past troubles for the black-operated and largely black-patronized establishment . We ordered a large pizza which was excellent but far more than we could possibly manage. We took our time over dinner, many patrons came and went and picked up take-out food as we ate. We relaxed afterwards, both of us feeling rather sheepish about the huge amount of extra pizza left in front of us and our inability to deal with it. Suddenly, a rather disheveled, obviously homeless white couple burst through the door of the restaurant. They were both unkempt, obviously in distress. They proceeded to dump their filthy clothing and various dirty plastic bags on an adjoining table. It was somewhat disconcerting, seeing two human beings in such bad shape, but a sight we had both seen many times before. Some of the discomfort of this encounter stemmed from our recognition of how very close we both are to the situation of being homeless people ourselves. We were reminded how close we all are to having nothing. Only those who have accumulated excessive wealth and privilege are afforded the illusion of immunity. A pang of avoidance swept through me in spite of my work in a homeless shelter in years past. The woman of the couple had an air of aggressive desperation about her that I instinctively knew would propel her in our direction, seeking a handout. Sure enough, she made a direct line for our table and asked in a rather incoherent manner if we would give her some food. We both reached for the unfinished pizza in front of us, and with our movement the disheveled woman instantly grabbed for the food before we had even lifted it off the table. She was desperate without doubt - demanding in fact - and when she spoke her mouth revealed broken, decayed teeth. Her clothing was filthy rags, an assemblage of discarded articles. As soon as she scarfed up our leftover pizza, she moved to the unoccupied table next to the one that they had dumped all of their belongings and filthy clothes on... her companion had disappeared into the men's room. Dakota also went to use the rest room. and I was left alone to watch the couple eating our leftovers. They ate with gusto, spilling food all over the table and lacing the pizza with huge quantities of Parmesan cheese and hot peppers. By this point, the manager of the establishment approached them and hassled them about eating there. He came over with a pizza box and told them that they would have to leave. He was kind enough to offer a box for their food at least. After a few words with them, he left in frustration and went in search of the armed security officer who had, for some reason, disappeared. Finally the manager located the guard, and he was brought over to the table and engaged the couple in conversation. Just then Dakota returned, and I motioned for her to sit back down with me to keep an eye on things. The couple was now eating in a frenzied manner in an apparent attempt to finish as much food as possible before being tossed out. I wanted to stay in case there was a need to intervene or explain the situation. We were the only patrons in the establishment, and the couple was likely to be treated more carefully than had we not been there. Our waitress came over to the table and asked how the woman had approached us. We explained what had happened and that we were perfectly comfortable with providing our leftover food to them. She explained that the couple had been making a habit of coming into the restaurant and aggressively asking for food from customers. I gave her one of my calling cards indicating that I was a “Reverend” and explained that there was no way I could have refused the request of another human being for food. She seemed to understand and let the matter rest. By this time, the couple had finished the food, and we decided to leave the establishment. Walking along the “Boulevard” Dakota remarked how their situation was only a small aspect of the bigger picture of the materialism and internalized oppression that permeates our society and is manifest in the quintessence of the prison culture. We talked about the mental health issue within the present system, with its total lack of real and meaningful community responsibility. Would such people, obviously seriously impaired through profound trauma, be reduced to living in squalor and chaos in a caring and supportive community-based society? I wondered what it would take to create an environment in which they could begin to heal from some of the severe damage and trauma that they had both experienced that brought them to their present state of existence. We walked back to our motel, I feeling uneasy about perhaps not doing enough, Dakota ruminating about not giving them some of our own meager funds. I told her that at least we had been able to offer them some food, which they obviously enjoyed, that we had made a gesture. On the way we stopped in a convenience store to pick up some coffee and bottled water. When we approached the store, a police officer was pulling out of the parking lot, having just had a conversation with a young, white woman working as a hooker. Inside, she was staggering around a coke display with a dazed look on her face, while we went to get our coffee, which had to be made fresh by an effervescent black woman who was the only clerk in the store. She was rushed but very cheerful and took her time in assisting us. As we were paying for our purchases, she was conversing with the young “working girl,” calling her “Racquel” and asking her if she was all right. It was obvious that “Racquel” was a regular in the store and that the clerk cared for her in an acknowledgment of sisterhood, solidarity in the truly revolutionary/enlightened point of view of seeing all beings in acquaintance with oppression. We are not two... We continued back to the motel and passed by one of the strip clubs called “Babes (The Name Says It All)” and saw a group of men hanging out in front of the place. Dakota commented how degrading for women and men the “sex trade” is and how pathetic that our society, in silence, and openly complicit, condones such exploitation and degradation. I thought of the culture that supports the men who own, run, profit from, and patronize such establishments and how this affects them also, how the oppressors are oppressed through their own actions “as the wheel follows the hoof of an ox pulling a cart” (Dharmapada I,1). The next morning I awoke early and walked down to the store to get morning coffee and juice to begin our long awaited pilgrimage day with Harada Roshi to death row. The clerk of the night before was long gone, and the store had a different atmosphere, that of working people in a hurry to get coffee on their way to jobs. As I left the parking lot, I noticed a young woman approaching. She had long blonde hair, an exposed midriff, and tight black pants with a draw-string closure. She greeted me with a big smile and a “look” and she appeared attractive to me. I responded with a cordial “good morning” as I passed by. I knew she was a working girl... having been around for a while, you get to know the routine. She was really putting it on, and I instinctively turned to look over my shoulder after we passed. Sure enough, she did the same, I instantly realized that I had “responded” as a typical male was socially programmed. I kept on walking but felt a little sheepish about the encounter, at least my reaction to her. I told Dakota about it when I got back and she asked me if I had engaged her in conversation, saying that it is not often that a woman working as a hooker can talk to a man without having the “business” end of it predominate. I guess I missed an opportunity... still, I was on a mission - a coffee run, the primer for a day so many of us had prepared for and worked so hard to bring to fruition.

Harada Roshi arrives:Venerable Shodo Harada Roshi’s flight was due in to the Memphis airport at 11:45 AM, and we were pressed for time in renting a car to drive the 156 miles to Tucker, Arkansas, the former plantation town that now houses the Tucker-Max Unit of the Arkansas Department of Corrections. We focused on preparing for the road trip. I had brought my “traveling zendo” kit, a black detail case that I've dragged into dozens of penitentiaries over the years, containing a Buddha image, an inkin bell, clappers, altar cloths, incense burner with a makeshift polyethylene cover held on with a broken and knotted rubber band, incense, charcoal, and other supplies used for performing various ceremonies and zendo events. We drank coffee and got our materials ready. Dakota not a Buddhist but a Revolutionary Social Activist with truly remarkable intuitive insight - and I an Irish American Rinzai Zen priest with a checkered past. Both of us broke. We were unable to rent a vehicle on arrival in Memphis due to lack of funds or a credit card so, we had to take the airport shuttle from the hotel to the airport and rely on our friends from Japan to take care of the vehicle rental. I have a distinct distaste for airport security checkpoints, which have proved troublesome in the past. For some time, the security agents manning the x-ray machines had instructions: a male traveling in religious garb was “profiled” as a person to be given “extra attention.” Entering prisons with the incense burner is sometimes a problem also - seeing a porcelain vessel full of fine white powder entering into a maximum security prison pushes a button in the minds of security personnel. We went to the gate where Roshi’s plane was scheduled to arrive, with about twenty minutes to spare. I was feeling somewhat on edge, which Dakota picked up on. She reassured me, saying... “relax and be yourself, you’ll be fine.” I had never met Harada Roshi before; this was to be our first encounter. I had not had much contact with Rinzai Zen masters other than through Eido Shimano Roshi’s visitors who came to Dai Bosatsu Zendo from time to time. Those encounters were different, however I was never in the position of acting as formal host. I had really very little background information on Harada Roshi, only a few descriptions from some American Zen teacher friends who had studied with him. Universally, they had told me that Harada Roshi was a very powerful teacher, known as the “master's master.” I had read a brief biography of him on the internet and seen a rather low-resolution picture of him posted on the site. I really had little to go on, and felt on the spot. I was aware of this all going on in the background, in the “small mind” and it was amusing watching it all happening at that level. I also realized the absolute absurdity of all of this chatter and knew at gut level that indeed everything was perfect - in, and of, itself. Roshi’s plane arrived a few minutes ahead of schedule and I waited at the gate to greet him. Dakota had a small disposable camera ready to take a few snapshots of our meeting. A number of passengers entered the terminal, and finally Harada Roshi walked through the ramp door. All my prior apprehension evaporated instantly at the sight of him. I felt an overwhelming sense of warmth and gratitude and bowed deeply as he approached. I was struck by his small stature I had, in my mind’s eye, I supposed envisioned a much larger man. This, I am sure stemmed from the preconceptions I had held based on what I knew of his reputation. Having finished my bow, I looked straight at him and found him smiling with great intensity, and I could feel a tremendous warmth emanating from him. He shook my hand - American style - said “Hello” and told me how pleased he was to see me. I sensed immediately a deep karmic connection with this man, something I had felt only twice before in my life, once with Venerable Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche and later with Venerable Eido Shimano, Roshi. Both of these men had been my teachers I wondered how this meeting with Harada Roshi would go. Directly behind him was Rev. Daichi Priscilla Kay Storandt - “Chisan” - the female zen priest who serves as his translator and the person I had been corresponding with for some time. Chisan was beaming and I instantly felt her warmth and her delight at seeing Roshi and me together, finally, after all of the preparations that had taken place to make this encounter possible. I was pleased to be able to introduce Dakota to Roshi and Chisan, the first Rinzai clergy people she had met other than myself. We were all smiling and felt good about being together, preparing to travel into the “belly of the beast” - death row, Arkansas. We were delayed at the airport for a short time because one of Roshi’s bags had been misplaced in Los Angeles where their flight changed over. Roshi and Chisan had come straight from a sesshin in Seattle and endured a long flight to Memphis. Within an hour, we had arranged for the rental of a mini-van, loaded all our bags and were on our way out of Memphis. I had brought my radar detector with me to use on the drive, but unfortunately the cigarette lighter did not work in the rental, so I knew I would have to be careful on I-40 driving through Arkansas. We were on a tight schedule and had a three-and-a-half hour drive ahead of us. I have driven the US Interstate system all over the country for years and have put in well over a million miles, I was sure I could shave our time down to at least two and a half hours, as long as I didn’t get “popped” doing ninety or a hundred miles an hour. Memphis sits on the Mississippi River, and we were afforded a grand view of the expansive river as we crossed over the suspension bridge on Interstate- 40. Roshi commented that he had never seen the Mississippi River before and that he had never been in the Southern part of the United States, only the North East and the North West. I was intently concentrating on the driving and content to listen to the conversation as it unfolded over the journey. After leaving Memphis, the first town we encountered in Arkansas was West Memphis, the location of the tragic and brutal murders of three eight-year-old boys killed on May 5, 1993. The murders took place in a wooded area bisected by a shallow creek just a few yards from I-40. As we approached the area known as “Robin Hood Hills” woods, I pointed it out to our guests. I had sent copies of the two documentary films, Paradise Lost and Revelations: Paradise Lost Revisited about the murders to Roshi in Japan a few months before. One of the men we were to visit on death row, Damien Echols, stood accused - and was convicted of, being the ring leader of two other teenage boys in the commission of this crime. Damien received a death sentence in the trial documented in Paradise Lost. The documentary raises profound questions as to his guilt and the fairness of the trial. As a result of the film and its impact, a significant support group has arisen around the case and the three teenagers accused. I remained intent on driving, knowing that the sooner we arrived at the facility, the more time we would have to spend with Damien and Jack Jones, another student of mine on death row. Dakota had a lot to say about the history of slavery and oppression that permeated the South and spoke extensively on these topics as the miles of Mississippi delta farm land rolled by. This conversation naturally turned to the present blatantly racist prison system, the proliferation of “private” prisons owned by huge corporations and “global economic” entities, the death penalty, human rights issues, and the systematically oppressive, power-over, coercive, and aggressive nature of American society. Roshi spoke about the death penalty in Japan, the secrecy surrounding its application, and the isolation of death row prisoners and even those who guarded them. He pointed out how the death penalty in Japan was a national issue and not done on a state basis, as it is in the U.S. He described the operation of Japanese police, stressing the thorough nature of their investigative methods. I was a little disturbed by some of his descriptions, as they seemed to indicate a high level of secrecy and compartmentalization within Japanese law-enforcement agencies. This struck me as a situation ripe for abuse and apparently lacking in rudimentary human rights protections. I talked with Roshi about various experiences I have had with American Buddhism and some of the questionable actions and practices of American so-called teachers. I told him about how I had felt about my own teacher’s use of the term “True Dharma” and that many years ago I had perceived this term as arrogant, but that over time I had gained a genuine understanding of the deep import of this phrase. We stopped at a gas station/convenience store in Arkansas to rest and purchase some snacks and beverages for the journey. We received some odd looks indeed. I have experienced this sort of reaction many times in the South, traveling in full monk’s robes. However, this time there were three of us in robes, which somehow seemed to make it easier. Harada Roshi was interested in obtaining a map of Arkansas to take back with him to Japan. We spoke further about the horrific incarceration rate in America, how 2 million plus of our fellow citizens are being imprisoned under deplorable conditions, increasingly in 23-hour-a-day lock down control units, where they sustain long periods of isolation and sensory depravation. This shocking reality is unknown to most Americans, yet its all pervasive growth and proliferation is eating away at our communities and destroying the lives of prisoners, families, and the extended community, in and out of prisons. The miles flew by quickly I was pushing a hundred miles an hour and we made good time in the new mini-van, it was a far cry from my usual mode of transport... a fifteen-year-old Volvo with no fourth gear and no air conditioning... we turned off the interstate and headed due south on Route 15 to Tucker. Along this stretch we encountered fields of cotton and soybeans stretching for miles in all directions. It was cotton harvest time in the parched fields. The plants stood as skeletons in the rows, their white puffs, or “boles,” of cotton starkly revealed. Periodically we encountered enormous standing bales of raw cotton placed next to the highway, waiting for pick-up by the cotton gin trucks. We mentioned to Roshi how, in the not so distant past, these fields had been worked by the sweat and toil of African men and women held in slavery. Much of the land we passed through had been plantation lands held by white land owners but worked and maintained by black slave labor. |

|

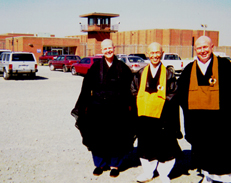

| Rev. Daichi Priscilla Storandt, Ven. Shodo Harada, Roshi and Rev. Kobutsu Malone - In front of Tucker-Max prison. |

| Photo By: Dakota Rowland |

Tucker-Max Prison:As we entered the town of Tucker, if indeed a general store and a bar could possibly be considered a town, we saw a sign informing us that we were coming into a penitentiary area and not to pick up any hitch-hikers. We turned left off the two lane highway onto State Farm Road, which led to the two Tucker prison units. As we came into view of the Tucker Max facility, we were assaulted with the view of modern slavery, rows of prisoners clad in “prison whites” toiling with hoes at the road side overseen by uniformed armed guards on horses. It was a haunting sight, a specter out of the South’s past rising before us as an indelible stain on our collective history. Many of these men doing forced labor before us, under the gun, were descendants of African slaves, “freed” men yet still unemancipated from the slavery of a racist prison system. This sort of work is considered acceptable to the people of Arkansas even though these days no modern farming or roadside maintenance requires this sort of punishing, back-breaking manual labor. It is not surprising to find it, though, in a state that has an official agency entitled the “Department of Community Punishment.” We pulled into the parking lot of the Max facility and got our materials ready to bring in, Dakota took a couple of snapshots with one of the two disposable cameras we had brought along in case we were allowed to bring them in with us. I was aware that we were possibly violating some facility directive but nobody even noticed. We had been refused the request to have a professional photographer accompany us and were unsure as to whether we ourselves would be allowed to bring in a camera. We were met at the reception building by the facility’s Chaplain Norman McFall. Chaplain McFall was new to Tucker Max. Chisan and I had had several email correspondences with the Chaplain, and I had sent him letters detailing the nature and significance of the lay ordination ceremony we were going to conduct. I also provided him with a list of the items we were bringing in for the event and all of our identification information to enable the department to run NCIC (National Crime Information Center) criminal background checks on all of us. All of the items in my “Zen kit” were examined and gone over thoroughly, each item being checked off on the master list I had provided months before. All was in order, and we were pleased to discover that there was no objection to us bringing in our disposable cameras. Each one of us was made to walk through a full-body metal detector, emptying our pockets of all their contents. Tucker Max had recently instituted a ban on tobacco in the facility, and we were asked if we had any tobacco products with us. The search was unusually thorough and incorporated a “pat-frisk,” which I had never had to submit to in the past when entering this prison. Having finished all these preliminaries, we were escorted by the Chaplain and a guard into the reception area and administrative office section of the prison. I had made arrangements with the administration to visit death row “cell-side,” an unusual accommodation , that I was unsure would be honored. I was pleased that we were told that this would indeed be possible and after turning over my “Zen-kit” bag to the front office staff we were taken through the internal security station consisting of two electrically operated, barred security doors enclosing a small chamber and admitted into the main corridor of the facility. Tucker Max is a relatively modern prison and fortunately has air conditioning in the cell blocks and general areas. This is a far cry from the conditions in which prisoners are held in other states and other facilities in the South. The heat conditions in the Florida and Texas prisons, for example, are torturous to those confined in them. In years past, prisoners have died due to the unbearable heat. In April 1999, I was part of a religious delegation with Sister Helen Prejean that was allowed to tour the Texas death row “cell-side” in Huntsville. The weather was not bad on the day of our tour, but we were able to see the inadequacy of ventilation provided in the cell blocks and had heard reports from guards and prisoners about temperatures reaching a hundred and twenty degrees on the upper tiers. Several men had fallen to the heat in the year prior, and one man had died as a result of his intolerance to high temperature brought about by the anti-psychotic medication he had been administered. Many men in both Texas and Florida are developing coronary trouble due to the excessive heat in these barbaric facilities. Tucker Max, however, was comfortable inside. The only area in the facility which is not air-conditioned is the disciplinary unit, the “hole,” which is used as a punitive housing area. Evidently, the punitive nature of isolation and sub-standard food rations is not sufficient “punishment”; it needs to be compounded by high temperature. As our group walked down the ten-meter-wide main corridor toward the “Five Pod,” death row, we were scrutinized by prisoners and guards alike. How strange we must have appeared, three of us in monk’s garb and Dakota in a bright flowered short-sleeved shirt with two and a half feet of yellow hair cascading over her shoulders. Dakota was concentrating on making direct contact with as many prisoners as possible, while I was paying attention to our guests and the arrangements with the administration. Security warnings about the possibility of rude comments were pointless, as we were greeted by all prisoners with universal respect. Dakota’s mission was to connect with as many of the mostly black men, in the prison as possible. Her simply making eye contact with them, smiling, and waving was a reaching out in solidarity to them, their response was in-kind and appreciative. Whether through a formal Buddhist ceremony or smiles and eye contact, the indomitable human spirit shines through. Even though we were visitors, people who would walk out of the maximum security prison at the end of the day, we were prisoners in there in terms of our movements, interactions, clothing, and demeanor, along side those men in the cages and with those in the uniforms perpetuating their imprisonment, a large number of them young female guards. In a conversation with a male guard Dakota learned that he lived very close to the facility and that working there was considered a good job in the community. Dakota asked if at any time anyone whom the guard knew from “outside” in the supposedly “free” world ever showed up on the “inside.” The guard returned a measured response stating, “I just try to treat them like human beings.” This answer revealed that this event was a fairly common and that he was somewhat uncomfortable with it and had been forced to come to terms with it. We arrived at the death row pod and were admitted through the security sally port into the floor of the pod. We were now in “the belly, of the belly, of the beast,” three tiers of steel cages designed to hold human beings uncompromisingly in isolation from the community and each other. I turned to Roshi and told him that every man in this unit had been condemned to death. I pointed out Jusan Frankie Parker’s cell, where he lived and practiced for so many years. We saw Jack first, standing at his cell door, wearing his wagesa and smiling. After looking around, we were able to spot Damien on the second tier at the far end of the unit. They had both been moved since my last visit, when they had occupied adjoining cells on the floor level. Preparations were made by the guards who had to go to each cell and handcuff Jack and Damien prior to opening the cell doors. They were then brought out to the pod floor, where leg irons were applied to their ankles and double security lock boxes were placed over their already double-locked handcuffs. During the minutes when cuffs and restraints were being placed on Jack and Damien, Dakota turned to the men in the tiers and worked on making eye contact and communicating with the prisoners in death row cages. One man asked her name, grateful for her response; another asked jokingly if she was a “Buddhist priest.” All the responses she received were warm and well-meaning. These men, mostly poor black men, were grateful to have some even fleeting communication with a human being not in the role of a power-over authority, brutal or otherwise. Jack and Damien had each brought his sutra book with him for the ceremony, and both of them were carrying small hand-made boxes. I was pleased to introduce both men to Harada Roshi, Dakota and Chisan. Jack and Damien bowed deeply to us all and were profoundly moved. They had both been looking forward to this day for many, many months. We were allowed to enter a very small chapel room situated just off the floor level of death row. There were folding chairs, and we sat in the confined space for our visit. We were joined by Chaplain McFall, who asked if he could observe. I made a brief introductory statement, and our meeting began. Jack presented Harada Roshi with his beautiful hand-made box, covered in Japanese-style pen and ink drawings. Damien presented his hand-made box to me and gave Roshi and me hand malas as gifts. I asked them, "What do you think, how do you feel?" Jack Jones replied to Roshi, "I am so nervous, I am very, very nervous. I don't know what to say to you because I am just so nervous." Damien, addressing Roshi, said, "I have been waiting so long to talk to you, I am so sorry because I wanted to ask this and that, a hundred questions, and now that I am with you my head is a complete blank I am so sorry, please excuse me." Jack then asked Roshi, "What do you think of this place?" Roshi responded through Chisan, "This place has an incredible sharpness; there is a very concentrated atmosphere here." Jack said, "This is a very concentrated place -a very instant - in here - every single day - every one day is this whole world." Roshi responded, "I have thirty students, and for all of them, each and every moment being the only moment there is the most important point." Jack answered, "For us there is no time whatsoever here. I read many books, but there is nothing in those books which compares to the depth that is in this one moment." Roshi said that is the way it is, and Jack replied, "It is because of my certain death that I have been able to realize this. If it were not for the fact that I am in these circumstances this would never have become clear to me. Every day I do zazen, and it is the most important part of my day. Everyday I do zazen on my bed facing the wall." Just prior to leaving the small chapel room, I asked Chaplain McFall if it would be possible for Harada Roshi to take a look in Jack’s cell to see how he lived and get an idea as to the size and layout of a death row cell. The Chaplain asked the ranking guard, and we were granted permission to visit Jack’s cell, which was at ground level and close to the chapel room.

Death row cell tour:We crossed the floor and Jack’s cell door was opened automatically from the main control room, a secure room isolated from the pod by ballistic glass and the only means of controlling all access, doors and gates within the pod. Entrance to the control room can be made only through the main facility hall way and is completely isolated from the pod itself. As we walked over to the cell, I jokingly motioned to Roshi that we had arranged for him to have an extended visit and gestured for him to enter first. He responded to my joke with his broad smile and obviously appreciated the energy of our collective spirit laughing in the face of execution. We entered Jack’s cell and looked around. It was a small space with a narrow vertical slit window, which admitted some natural light. There was a narrow bunk bed with a thin mattress and a writing desk and built in chair next to it. The front wall of the cell, closest to the cell door, had a small stainless steel toilet/sink appliance ,which enabled the commode to be used with the prisoner facing into the cell but still enabled anyone outside the cell to observe the prisoner at all times... there was no corner of the cell that could not be seen from the barred cell door. Jack had a small shrine set up on his desk and a number of photographs of his two boys and of a woman he writes to in Holland mounted to a piece of cardboard over his desk. We all looked at the photos and Jack explained who they were. It was crowded in the confined space, and I am sure it was a truly unusual event to be taking place on death row. Two large guards stood by at the door of the cell, keeping an eye on everything that was taking place. Having finished our “tour” of death row, we were all brought through the security sally port back into the main hall. Jack and Damien were escorted to the entry to the visiting room from the main hall way, and the rest of us were brought through the main-entry security check point to enter the visiting room. |

|

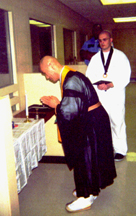

| Ven. Shodo Harada Roshi, and Koson Damien Echols during the Jukai Ceremony in the prison visiting room. |

| Photo By: Dakota Rowland |

Jukai Ceremony:My black bag “Zen-kit” was placed in the visiting room, and we were admitted through a barred gate into the area. There were a series of windows on both sides of the long visiting room, and there were several people we had not seen before behind them watching us as we entered. I chose one of the visit cubicles directly on the spot where Jusan had received Jukai four and a half years ago and began setting up an altar to be used for the ceremony. I had brought everything we could possibly need, and we prepared a nice altar arrangement on a pure silk altar cloth. I had purchased a supply of extra fine “jinko,” an extremely expensive and rare natural wood incense for the ceremony. Our altar consisted of a carved wood Buddha (given to EZF by Hozo Jack Van Allen), a ceramic incense burner, a ceramic water offering bowl, a candle stick and white candle, a rin and inkin bell, and two shiki-shi calligraphic pieces done by Harada Roshi as gifts for Jack and Damien. Harada Roshi also brought from Japan two beautifully made Rakusus, inscribed with their new Dharma names. I had made rings for the vestments from pieces of spaltered maple wood, which was harvested from the forest surrounding Dai Bosatsu Zendo, my home temple in Livingston Manor, New York. I gave a Jukai exhortation written by Venerable Eido Roshi based on the Dharmapada XIV. 4 It was through a dog-eared copy of The Dharmapada, thrown with contempt on the floor of an isolation cell in “the hole,” that, with its first reading by Frankie Parker twelve years ago, changed his life so profoundly. Each man, Roshi, and I offered incense, and we chanted: The Purification (Sangemon), The Three Fundamental Precepts, Tisarana (Three Refuges), and The Ten Precepts. Incense in prison is a rare treat indeed for prisoners. Prisoners are prohibited from possessing or burning incense in their cells even as part of their religious practice. In Tucker-Max, with its “no-smoking” regulation, there is no need for prisoners to have any matches or a lighter, so these items are also prohibited in the name of “security.” Harada Roshi, through Chisan’s translation, explained the two Dharma Names, then blessed and presented a black rakusu to each man. Damien received the name Koson meaning “Respect for, or devotion to, or searching for, the light,” and Jack received the name Dainin ,meaning “Great patient forbearance.” We then chanted The Four Great Vows for All three times in Japanese and once in English. I made a closing remark and our ceremony was complete. At times during the ceremony I had to assist each man with his Sutra book because of the shackles, which bound their hands together. We were not able to perform the ceremony at floor level because we were not able to bring in sitting cushions and mats. Jusan Frankie Parker had been allowed to at least have his hands free, although he always was leg-shackled during our contact visits. Dakota related to me later how she had noticed that the sharp crack! of the clappers produced a pronounced stiffening of the guards present in the room. I took each man aside from the group for a few personal words as the others gathered around Roshi and talked. This had been the first opportunity I had in over eight months to see them face to face in private. We walked to the end of the corridor, being certain to remain in the sight of the four guards present in the visiting room. I asked them both men to write an account of the encounter while it was fresh in their minds. Chaplain McFall had many questions for Roshi... he asked why we shaved our heads. Roshi responded... “to remind us that we really want nothing.” I couldn't resist rubbing my head and commenting, “How come I still want a Harley Davidson?”... we all laughed. It was hard saying good-bye, but we were limited by time and unsure as to the possibility of seeing two other Buddhist prisoners. Jack and Damien both bowed deeply and embraced Harada Roshi as we parted. Roshi, Chisan, and Dakota went to the Chaplain’s office while I exited the facility with an escort so that my “Zen-kit” could be placed in the mini-van. On my return, as I was being taken to the Chaplain’s office, I ran into Bobby Fretwell, a Buddhist prisoner who had received clemency from the governor and had had his death sentence commuted to life without parole a week before he was to be murdered. Bobby had been close with Jusan, “Si-Fu” as they knew him then. We went into the Chaplain’s office and found coffee. I made introductions for Bobby. Dakota asked Bobby what he did for a job, and he told us that he worked on a hoe squad for eight hours a day. She then asked if there were any options to performing such back-breaking work in the heat and blazing sun. He said he really did not have any choice in the matter, the alternative being punishment in the hole. We bid farewell to Bobby and Chaplain McFall. On the way out of the unit we were delayed shortly, waiting for a barred security gate to open. Dakota and I noticed the prison shoe-shine shop adjoining the area and we put our heads in the door and saw a black prisoner intently shining an officer’s boot. Around him were arranged several officer’s boots, all shined and buffed. I said to him, “Shining the man’s boots, huh?” He said, “Yep!” and I said to him, “Be sure to give them a spit and polish shine... heavy on the spit.” We all crackedup over this... no harm was done, the boots got shined, and three people fell together in a single moment, shared our common recognition of our communal anger, experienced a moment of solidarity, and parted as changed beings.

On the road again: We left the facility... the hoe squads long brought in and locked down - and got back on the road to Memphis. Roshi and Daichi had a plane to catch and had to be at the Memphis airport at 6:45 AM. Our trip back was quieter, Roshi took notes in the back as I drove through the miles of darkened interstate. We arrived in Memphis late, our guests eager for rest, with a long day ahead of them and a training sesshin to face in two days. In the morning, I drove them to the airport for their flight. As he was leaving, Harada Roshi said to me that he “would come back.” I felt relieved I knew he was affected and I knew that through this man would flow true Dharma into the “Belly of the Beast.”

Conclusion:The essence of this remarkable teaching is that there is an alternative to death row. There are alternatives to all of the other manifestations of oppression chronicled in our story. DEATH ROW AND PRISONS DO NOT EXIST IN A VACUUM. When we ourselves do not live in a state of sustainable harmony with each other and our surroundings, we mirror in our individual spiritual, mental, and physical health that lack of community - that “dis-ease” that perpetuates our system of oppression and keeps us asleep. We need to awaken to the predatory, power-over, “globalization” and “technology without question” dynamic that permeates our society. Venerable Harada Roshi’s pilgrimage to death row is an invitation to all of us to “Wake up!” to look deeply and see things clearly, to walk on the path of the awakened state of mind, in solidarity with our sisters and brothers, with all beings, to work in dynamic peace for the non-punitive community circle dynamic as practiced through the restorative-justice alternative to the prison industrial system and which is being fostered, revived and kept alive within indigenous communities.

Addendum:This story is written in journal form as an expedient medium for including our observations, reactions, thoughts and feelings, through our encounters with all the men and women we met throughout the pilgrimage. We are concerned that what is missing here - what we may have failed to relay to you - is the all-encompassing horror of the scapegoating, punishment/vengeance -based, and racist “prison system” in operation throughout America today. Words can not convey the intense personal pain, degradation, torment, and torture encountered daily in our prisons. In a way, our account may present a voyeuristic picture, a narrative that falls short in conveying the intense feeling of tangible, palpable fear that pervades Tucker-Max and all other prisons where human beings are incarcerated as punishment for deeds judged by others. No words can approach the reality of prison life - the smell of terror, that distinctive, all-pervasive, odor of oppression. It is easy to sit on a cushion and read our account, yet inevitably some of you reading these words will, at some point, find yourselves in prison, experiencing the horror first-hand. Any one of us could find our selves accused, convicted, and sent to prison at any time. So let’s rid ourselves of any notion that it’s “them” in prison and “us” out here. Ain’t like that...

For more information on this article please refer to:http://www.users.aol.com/muryo/teacher.html http://zen.columbia.missouri.org/wayofzazen.html http://www.qwikpages.com/backstreets/standingdeer/bonniekerness.htm http://www.shambhalasun.com/Archives/Features/2001/Jan01/rowroshi.htm http://www.arktimes.com/archives.htm#witch http://www.arktimes.com/trial1.htm |

| Suggested Reading |

| RESTORATIVE JUSTICE: THE ROLE OF THE COMMUNITY |

PUNISHMENT |

| by Paul McCold, Ph.D | by Ven. Kobutsu Malone, Osho |

| http://iirp.org/library/community3.html | Kobutsu-Punish.html |